Brain Drain 🇨🇦

Yes, it's a problem

Canadian brain drain has been a hot topic for decades. We’ve worked our way through the Five Stages of Grief over the past 20 years: Prime Minister Jean Chrétien famously dismissed the brain drain as a myth (denial) and now we’ve moseyed our way to acceptance—yay.

Even with this newfound acceptance, policymakers haven’t rolled out any measures to better retain Canadian talent. We know it’s an issue but are just too busy to deal with it. It’s possible that it’s simply not a big enough problem for politicians to tackle. Or, people are failing to recognize just how big of an issue this really is.

Having studied at the University of Waterloo, I’ve seen the scale of the brain drain first hand: ~90% of my closest friends now work internationally (primarily in the US). Why? Salaries are at least 2x higher in software & finance jobs, healthcare is much better, especially when you have top notch insurance (which you would get), there are more opportunities to grow your career…I could go on. Obviously, it’s not all sunshine and roses but you get the picture.

I’ll spare you the anecdotes and let the data speak for itself.

Why are people leaving?

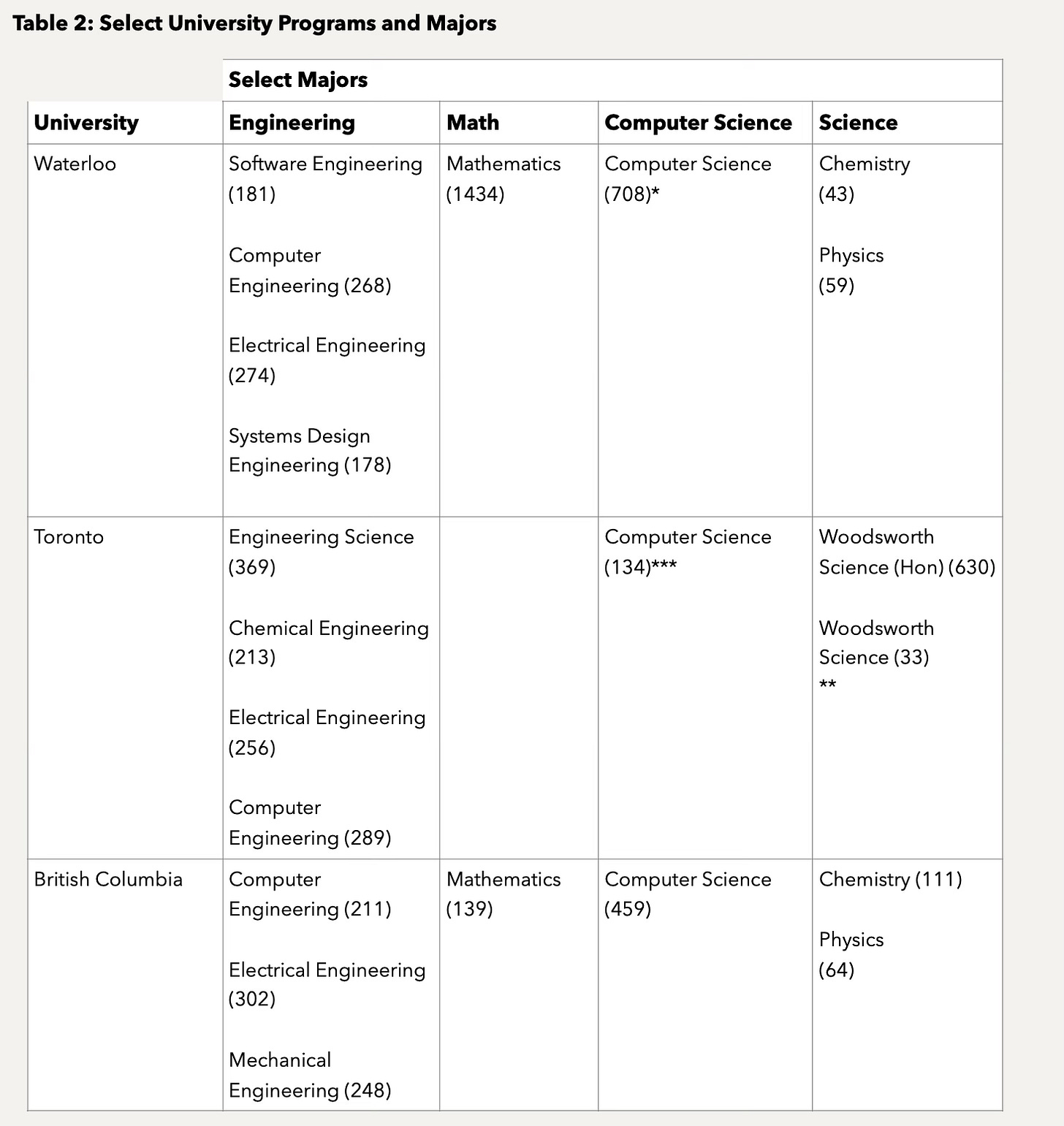

Let’s start with a survey from the CS class of 2023 from the University of Waterloo.

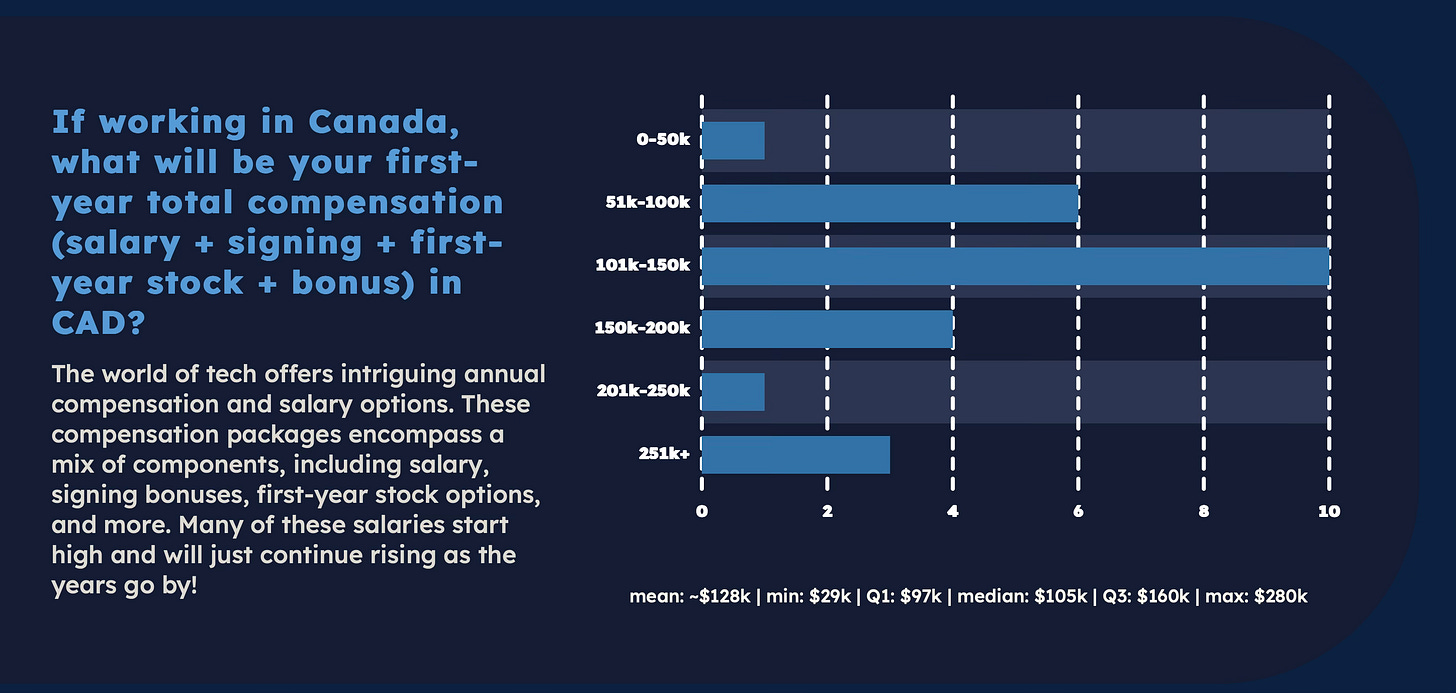

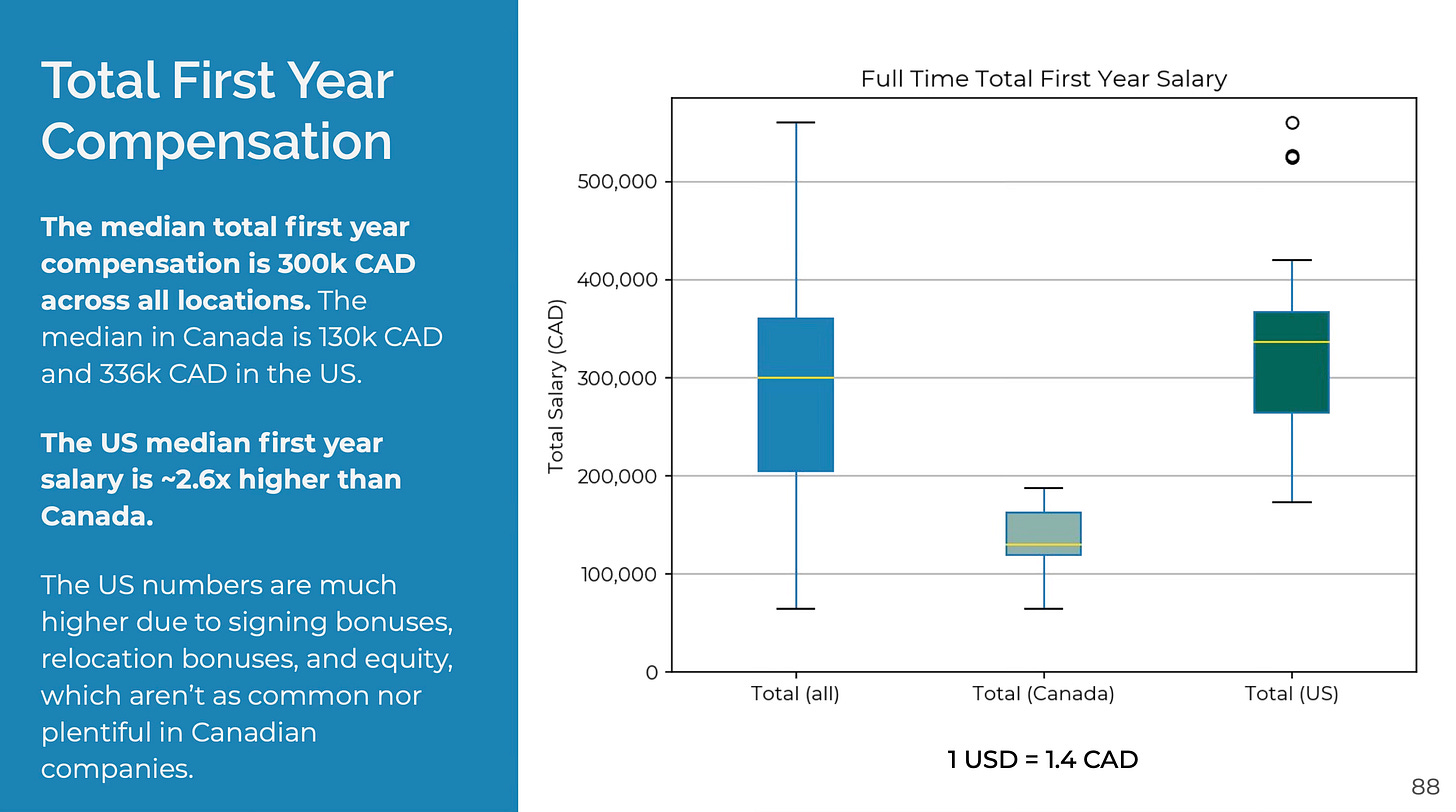

The disparity in the earnings distribution is wide. Median total compensation is ~3x higher in the US. The minimum reported total comp is ~6x higher in the US. Maximum total compensation out of school tells a similar story. Maximum compensation right out of school can be upwards of $800k compared to ~$280k in Canada. Granted, only a handful of students would earn in this top US income bucket at firms like Jane Street, HRT, and Jump (to name a few).

The software engineering 2020 class profile has even more granular insight.1

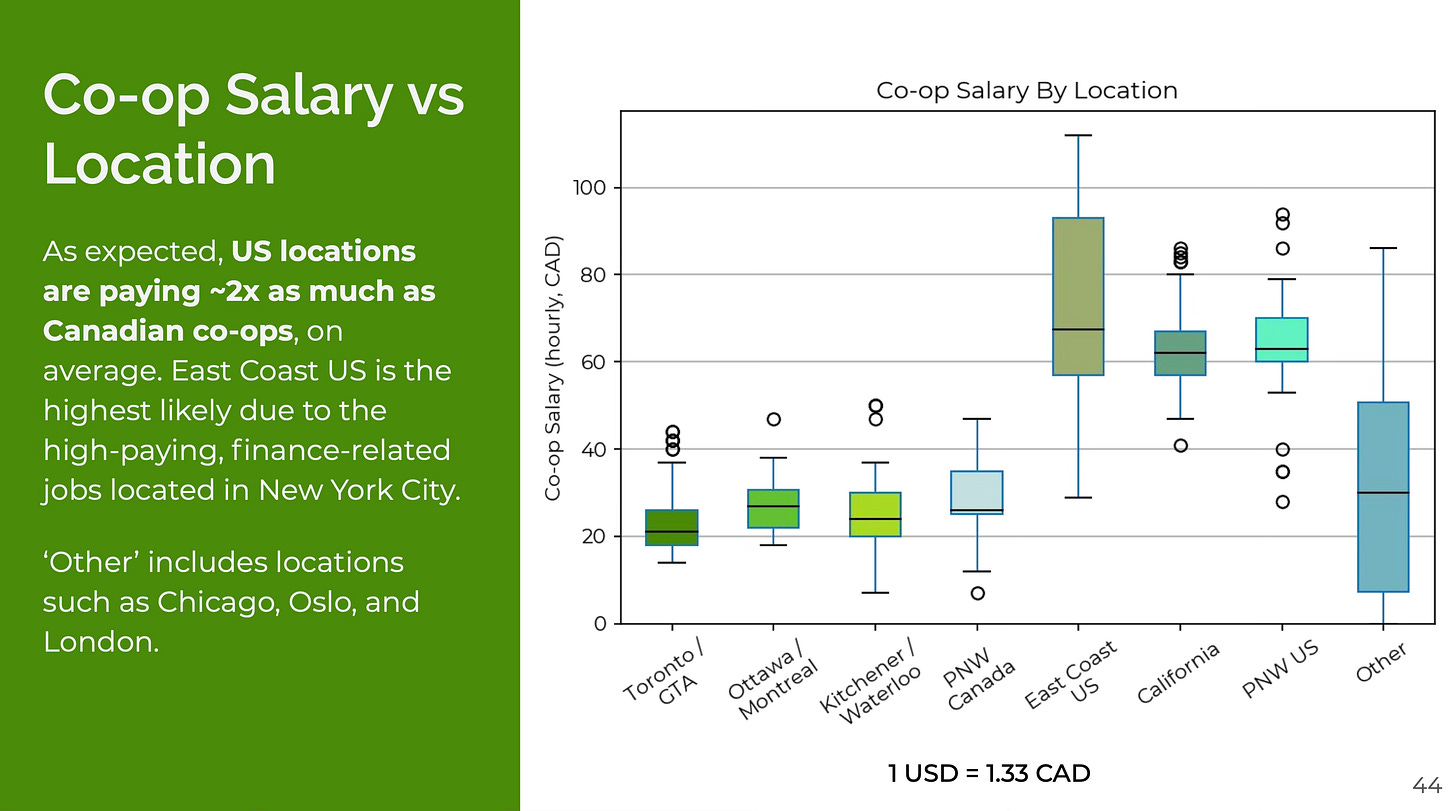

These stats are in line with the 2023 numbers above. I suspect these 2020 numbers show higher averages given the COVID hiring boom. This pay disparity doesn’t fall out of the sky come graduation time. Students see this from the very beginning of their undergrad journey.

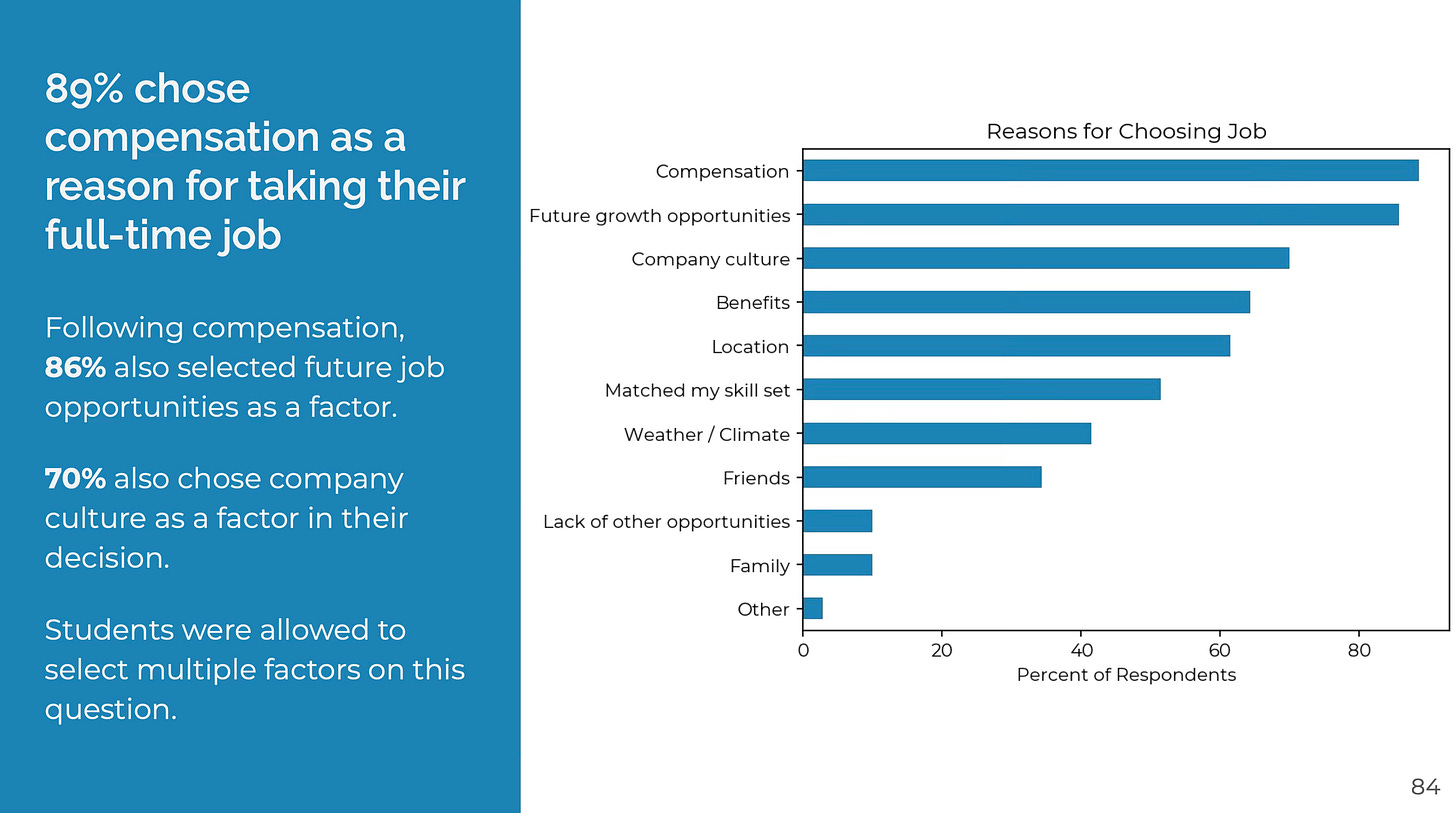

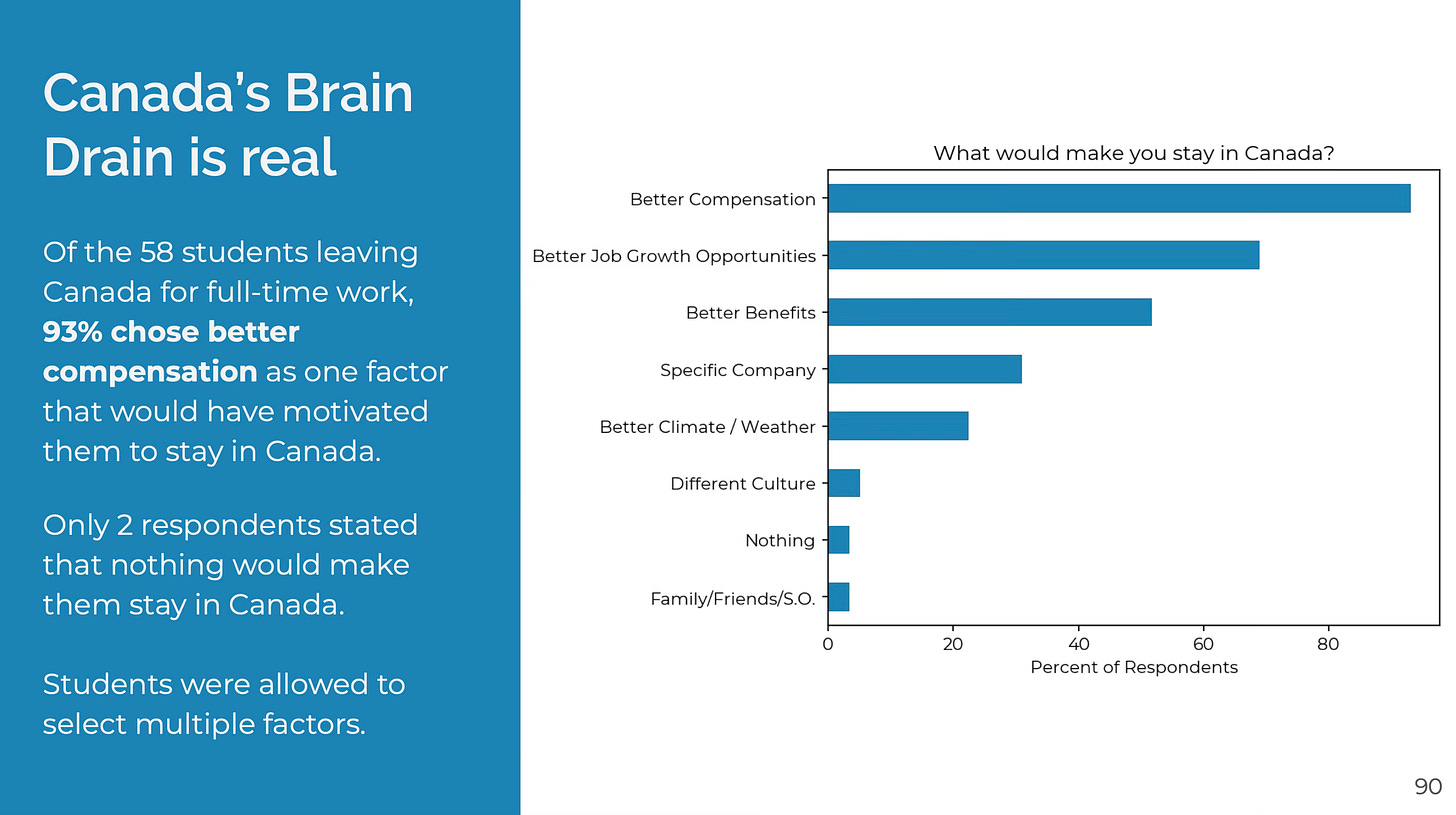

What undergrad wouldn’t want to work in the US over Canada? Compensation is a no brainer. Students build their professional networks in the US. Stack up a couple internships and it’s only getting more likely to get a full-time offer to go back. Unsurprisingly, compensation is the #1 reason students choose to leave Canada.

Waterloo students become aware very early of what they can be worth and they’re not afraid to maximize that number because all of the top companies in the world come to campus every term to attract students. There’s a tendency to not self-select yourself out of opportunities. When you see your friends landing great jobs, you believe that you can do it too.

Students aren’t oblivious that they’re a part of the brain drain. They’re acutely aware, but they’re not presented with rational reasons to stay.

Like I mentioned above, compensation, better growth opportunities, and better benefits are the top reasons for leaving Canada.

It’s worth addressing that the salary numbers I’m citing are not typical US salaries. The average software engineering salary is in the $130,000 range. That’s a great income, but less than the stats above. The students answering these surveys are the top students from the top programs getting hired by the top companies who are willing to sponsor work visas.

That being said, that discrepancy in opportunity for the best students is the problem. Aside from a handful of firms, you can’t make $200k+/year in Canada out of school. Yes, I realize that’s an absurd statement to make when the median Canadian salary is $43,100, but in a world where technology drives innovation & prosperity we’d ideally keep more of this top tier talent in Canada.

In an opinion piece in the Toronto Star, Bilal Akhtar, a 2019 Waterloo software engineering grad, tackled this point head on:

I’m used to seeing my friends pack up bags and move to the United States. Most of my graduating class of software engineering at the University of Waterloo decamped for the U.S. right after graduating in 2019. The few who stayed back, have strongly considered moving or have gradually made the jump since.

Consider the recent artificial intelligence (AI) boom that’s centred around San Francisco-based companies like OpenAI and Anthropic. Some of the most notable academicians in the fields of AI and machine learning, such as Geoffrey Hinton and Ilya Sutskever, hail from the University of Toronto. We’ve just failed to build a big enough ecosystem around any of that. The $200 billion (and growing) AI sector could have had a bigger presence right here — instead of being mostly on the other corner of the continent.

If you were to ask people directly why they left Canada for the U.S,, the usual responses are: higher pay, better work opportunities, and community/friends making the same move. Secondary traits like weather rarely register as common reasons.

Tech workers in Canada generally earn about 46 per cent less than in the U.S. The trend is similar outside of tech, with incomes generally higher in the U.S. Most people are OK with a pay cut if it still gets them a high quality of life. But with the skyrocketing cost of housing in cities like Toronto and Vancouver, job offers north of the border are increasingly becoming less competitive. Until housing supply catches up, the difference in incomes is only going to sting more.

Per his LinkedIn, he has since relocated to the US.

To clarify, if you look at the methodology of the study he cites, the 46% number comes from comparing average Canadian salaries to average US salaries. Again, this average-to-average comparison is interesting but this isn’t the choice that top Canadian STEM students are faced with. They’re weighing offers that will pay on the order of 2-3x more if they move down south.

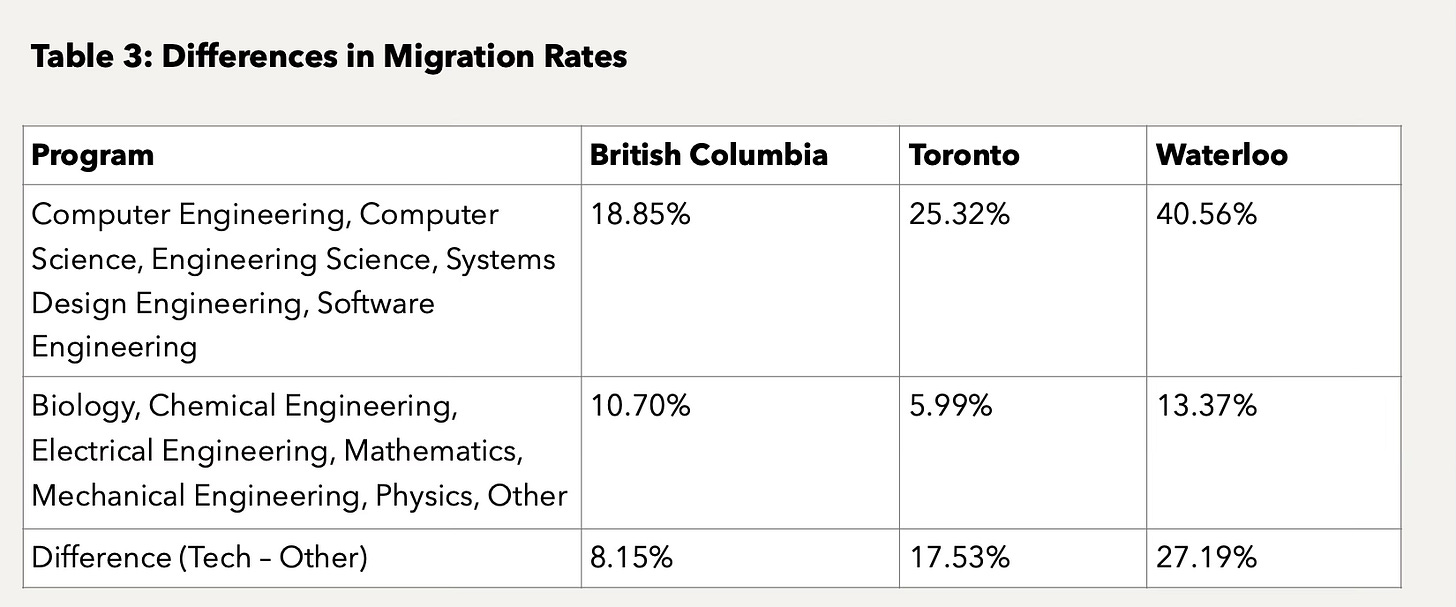

All that being said, tech folks are often the highlight of brain drain stats, but it’s more widespread than that. Reversing the Brain Drain: Where is Canadian STEM Talent Going?—one of the most comprehensive analyses published more than 10 years ago—shows us why. Succinctly, it’s important to account for absolute program sizes. While large proportions of software/CS students emigrate, these programs are relatively small compared to their other STEM counterparts.

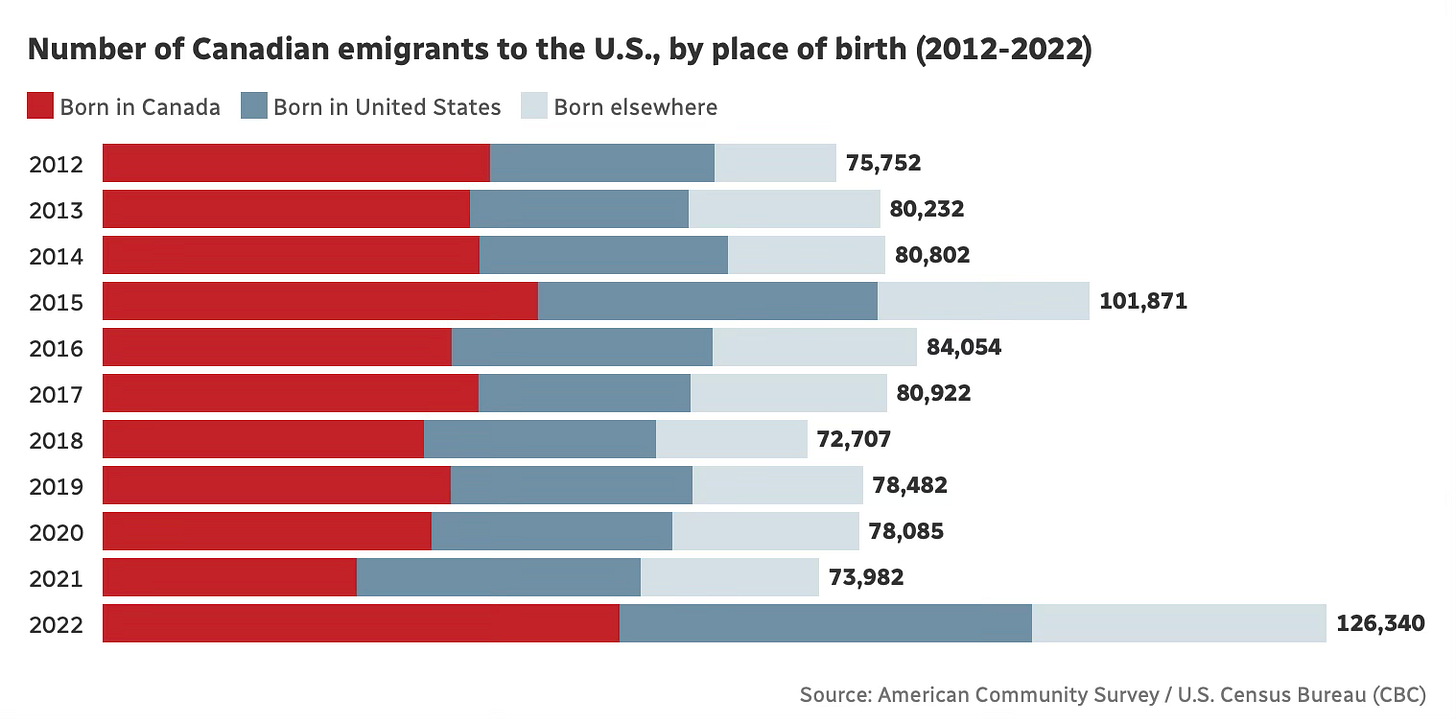

It would be easier to just tackle why software engineers are leaving Canada, but the allure of American jobs exists not only with new grads, but with professionals across the board: the ACS, which is conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, says the number of people moving from Canada to the U.S. hit 126,340 in 2022. That's an increase of nearly 70 per cent over the 75,752 people who made the move in 2012.

What are we actually losing?

It’s one thing to say Canada’s losing a lot of smart people but can we make this more meaningful?

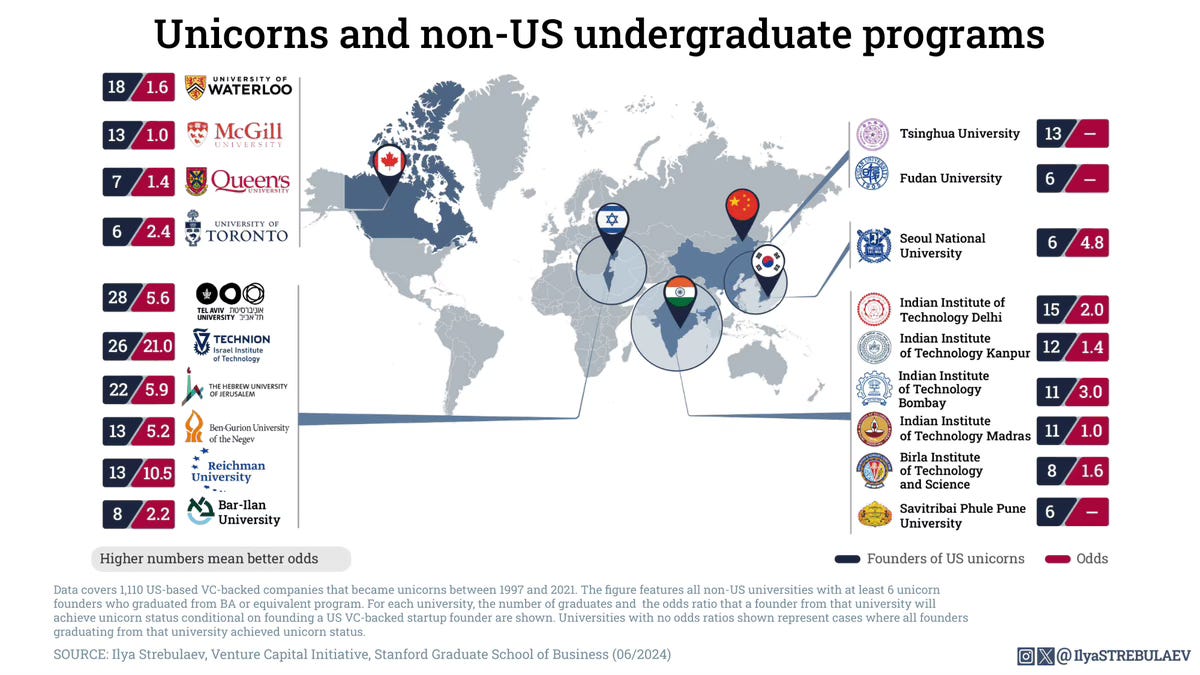

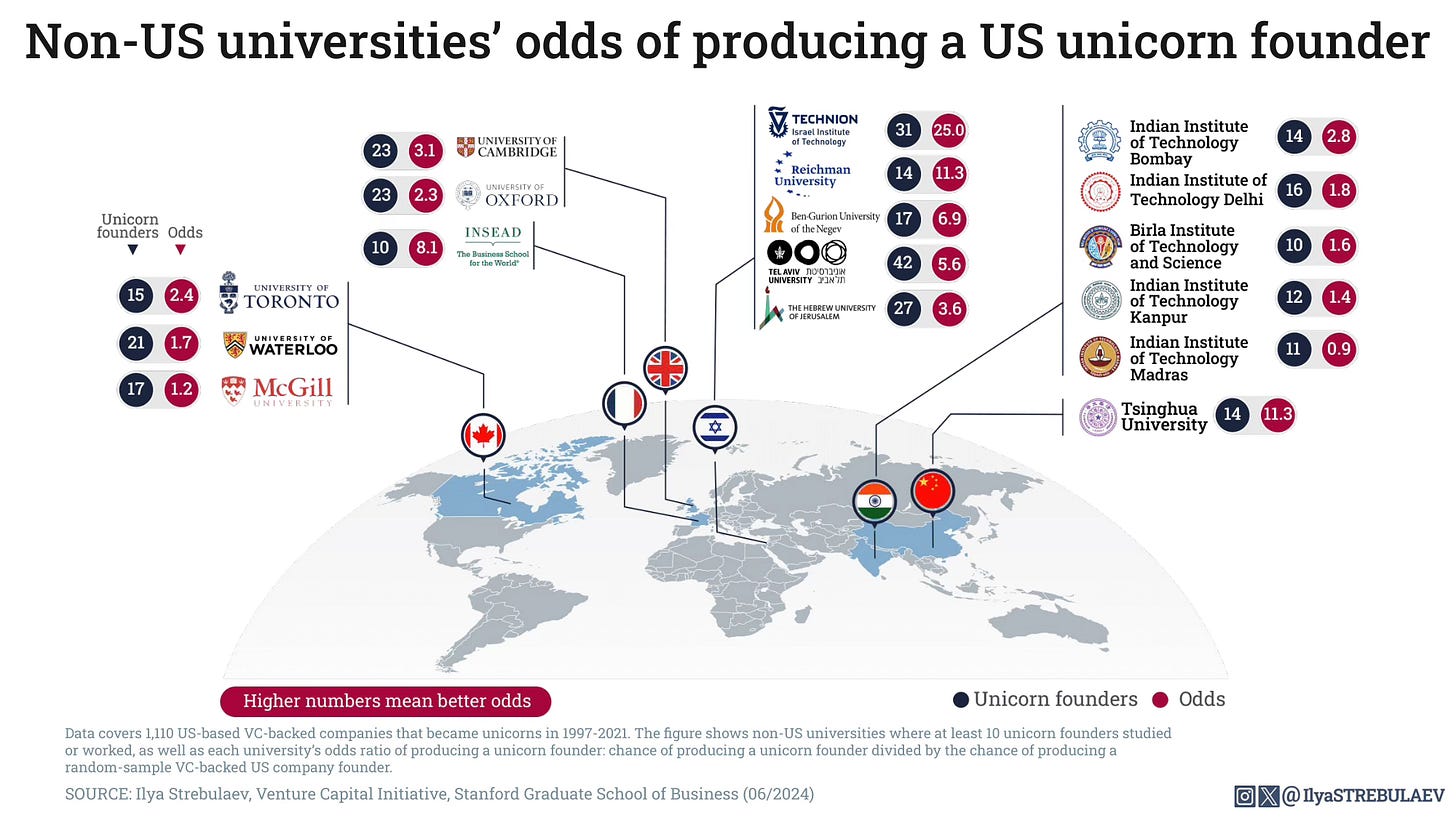

Stanford Business School professor, Ilya Strebulaev, has some informative tweets that nudge us towards an answer.

Between 1997-2021, Canada produced at least 53 founders that founded unicorn companies in the US. As of April 2025, Canada has had 31 unicorns to date. At worst, we’ve exported 53 unicorns down south. More conservatively, assuming these 53 founders worked in pairs, we’ve exported 26 unicorns. No matter how you think about it it’s a stark number: we’ve shipped out at least 50% of our highest growth tech industry.2 These stats are just focussed on the largest tech startups, so we’re omitting many Canadian success stories, but these are alarming figures regardless.

We can put these figures into more context. The US has about 1000 unicorns, so that means around 1-in-20 US unicorns are Canadian-founded. Mind-blowing. It’s a testament to the calibre of Canadian talent, but that’s a tough number to read if you’re someone who wants the Canadian economy to grow. I’m harping on this point because there are long term network effects to these successful outcomes. People leave these startups to create their own companies and that cycle repeats. The PayPal Mafia is an outlier example, but it shows the value that successful startups have in fostering new ambitious projects; we’re missing out on these anomalous outcomes and we’re not collecting the ingredients needed for a growing tech industry.

My gut feeling is that it’s only going to get harder to catch up. As an example, all of the frontier AI/ML labs are within 50-square-miles of each other in the Valley. That’s not a coincidence. It’s the result of decades of innovation in a concentrated geography. It’s compound interest. Those are entrenched ecosystems you can’t disrupt easily; innovation is sticky and it’s a magnet for other like-minded people.

Geoff Ralston and Michael Seibel wrote:

It is very difficult as a new startup founder not to obsess about competition, actual and potential. It turns out that spending any time worrying about your competitors is nearly always a very bad idea. We like to say that startup companies always die of suicide not murder. There will come a time when competitive dynamics are intensely important to the success or failure of your company, but it is highly unlikely to be true in the first year or two.

When competition does start to matter, is there momentum in Canada’s favour? Canadian companies have to fight for talent that can compete globally and I don’t know if that’s getting easier. Canada’s competing with companies around the world: if your aim is to be the best in the world, your competition isn’t in Canada.

How do we fix this?

I don’t see a short term path to retain Canada’s top STEM talent, so we can do our best to attract talent that doesn’t want to live in the US.

Net immigration numbers show promising trends. High Skilled3 immigration alone makes a big dent in compensating for US emigration.

In 2023, the Government of Canada (GoC) piloted an immigration program targeting H-1B visa holders to settle in Canada so they wouldn’t have to deal with the American immigration system. I thought this was an amazing idea! Naturally, the last update for this program was two years ago and I don’t think GoC is pursuing this anymore.

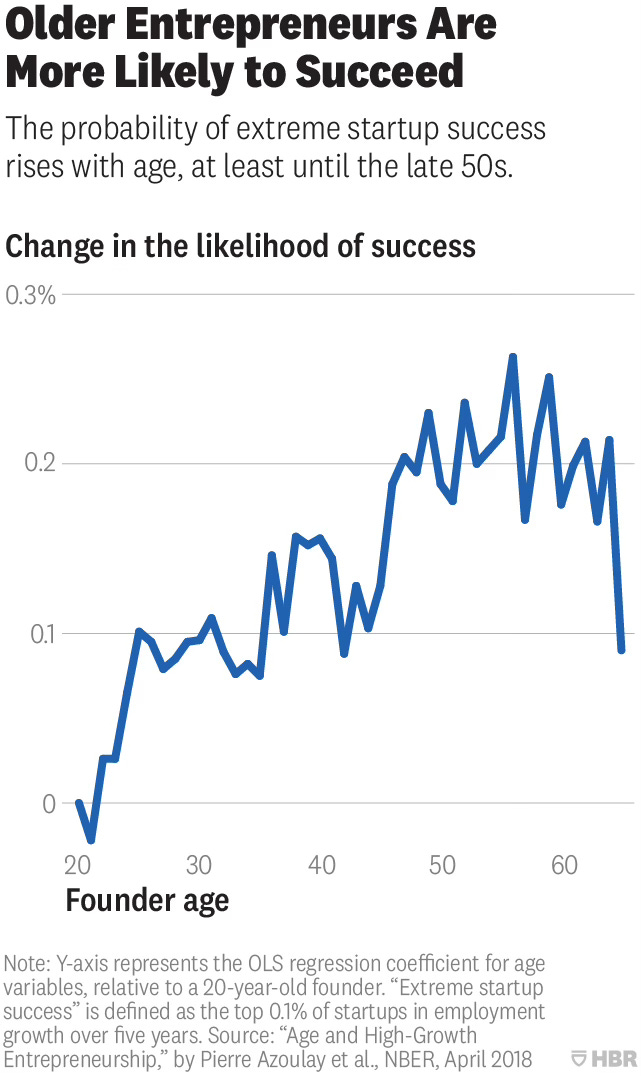

The potential 2nd order effects of policies like the H-1B program are notable. According to the Harvard Business Review, older founders have higher probabilities of success. The instinct to attract more experienced talent could be a winning idea.4 Time will tell.

There are some no-brainer changes that could help. If you don’t mind I’ll put my Prime Minister hat on for a moment.

Grant automatic permanent residency or citizenship to international students in top STEM programs. Entice students with the option to stay where they went to school.

Improve government procurement. GoC shouldn’t purchase competitive technologies from other countries when superior (or equivalent) Canadian products exist.

Continue strengthening the SR&ED program.

Make it more attractive for companies to be in Canada. Amazon’s expansion in Vancouver is a good model. There’s generally an allergic reaction to incentivizing big companies to move into cities but I don’t see a more impactful way to spur local economies and train talent that may one day take a leap of faith to pursue their own ideas. With more talent and more local competition we could see salaries become more competitive. One day, new grads may not have to take huge pay cuts to stay in Canada.

My biggest fear is that in 20 years nothing would’ve changed and we’ll be in the same boat. In 2003—22 years ago—Stan Uhm wrote:

Alexander Graham Bell was one of Canada's greatest inventors, James Gosling invented the computer language JAVA, the language that is slated to revolutionize computing, and Nobel economics laureate Myron Scholes, is a venture capitalist and professor Stanford University. Surprisingly, these 3 people have a few things in common, one being that they are all Canadians. Another thing they have in common is something that is becoming a trend. They all left Canada to further their work in the United States of America (Purvis 46). Every year, thousands of our doctors, scientists, nurses, engineers, and other professionals migrate to the United States in search of higher wages, lower taxes, and enhanced opportunities.

In another 22 years, I hope we won’t be writing the same thing.

Unicorns and non-US undergraduate programs: Data covers 1,110 US-based VC-backed companies that became unicorns between 1997 and 2021. The figure features all non-US universities with at least 6 unicorn founders who graduated from BA or equivalent program. For each university, the number of graduates and the odds ratio that a founder from that university will achieve unicorn status conditional on founding a US VC-backed startup founder are shown. Universities with no odds ratios shown represent cases where all founders.

Non-US universities' odds of producing a US unicorn founder: Data covers 1,110 US-based VC-backed companies that became unicorns in 1997-2021. The figure shows non-US universities where at least 10 unicorn founders studied or worked, as well as each university's odds ratio of producing a unicorn founder: chance of producing a unicorn founder divided by the chance of producing a random-sample VC-backed US company founder.

Lastly, given that Israel has a population of around 10M people, their stats are absolutely astounding.

Includes admissions in the Federal Skilled Worker Program, Federal Skilled Trades Program and Canadian Experience Class.

Forgetting about entrepreneurship for a second, bringing experienced talent to Canada is a net positive no matter what: existing companies benefit from global expertise, GoC gets more assets to tax (great for one side of the equation), and it opens the door to bring in more doctors and specialized professionals in areas where Canada is lagging.

Excellent research !

This is an amazing post, very well researched and articulated. Kudos